Laconia Therrio remembers many things from his time at Harding College, where he enrolled as a freshman in 1972 and would later be elected by the student body as Student Association (SA) president in 1975.

He remembers the anthem for the men’s social club of which he was a part. TNT gave him some of his fondest memories — memories of positive influence, brotherhood and a strong competitive spirit against Chi Sigma Alpha in Spring Sing.

He also remembers babysitting for a handful of his professors and finding a chance to play pool against them, too. Joe Pryor was a physics professor, and while Laconia thought his pool-playing talents were strong, he rarely stood a chance against Pryor.

“He didn’t play pool very much, and I was a fairly good pool player, but Dr. Pryor was a physics instructor, and he’d kick our butts,” Laconia said. “You could literally almost see him looking at the angles and lines on the pool table. When we saw him do that once, we knew we were sunk. That’s one of my most indelible memories.”

Boys in blue, Spring Sing, devotionals around the lily pool, relationships with professors — he recounts them all fondly. But he also recounts a strong naivete that marked his Harding years.

“I think, in 1972, I had a tremendously idealistic view of Christianity — that if you had the word Christian associated with you, you were not going to be affected by how the world is,” Laconia said. “I think over time, I gathered that was tremendously naive.”

“I think, in 1972, I had a tremendously idealistic view of Christianity”

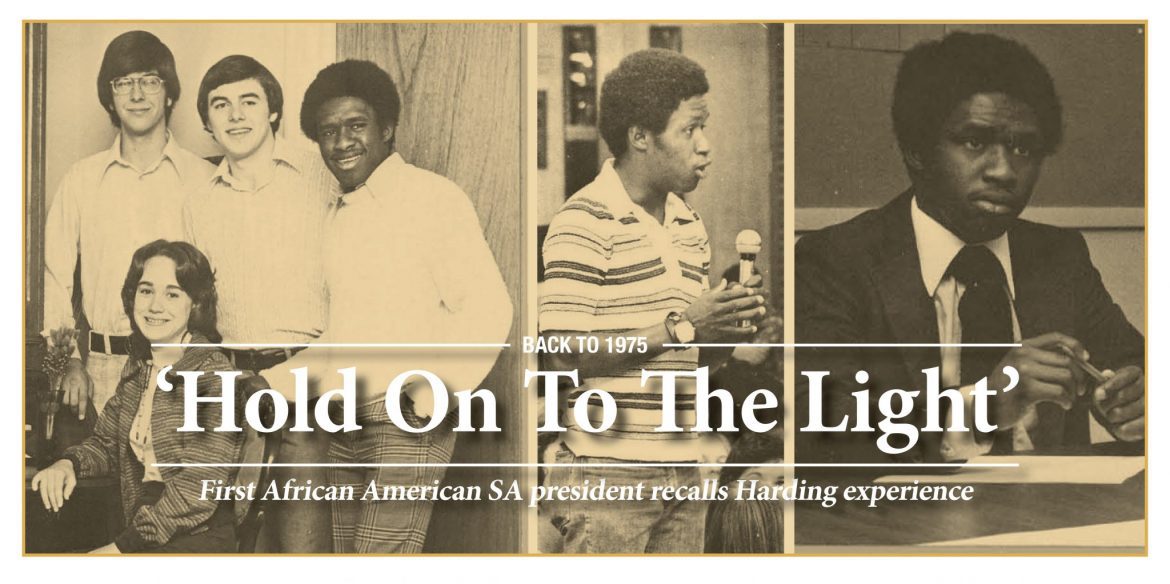

When Laconia was elected to serve as SA president during his senior year, he was the first African American student to be elected to the office. Laconia coasted to victory with 1,072 votes over his opponent’s 257, wide margins for a race that came only 12 years after Harding College had admitted African American students for the first time.

It had also been just seven years since the assassination of civil rights activist Martin Luther King Jr. and six years since the integration of schools in his hometown of Gretna, Louisiana. The Civil Rights Movement was still fresh in America’s collective mind.

Laconia admits that looking back, the historical significance of his race for the SA’s top position and his time at Harding was not fully realized.

“I certainly wasn’t aware of that history at the time,” Laconia said. “I imagine, had I been aware of that history, it may have been a little overwhelming. I think I was pretty naive. I ran on the basis that I knew people, and I think, to some extent, people knew me.”

But his naivete found solace in kindness — in the people he knew and the people that knew him — even when the evils of society surfaced.

Laconia is candid about not-so- fond memories at Harding, memories that would be balanced by kindness and memories that are “a big part of [his] story since then.”

He remembers that students asked him to quit the race when they found out his campaign had put up signs just an hour before the official campaign start time. He did not, obviously, quit the race, and he said he did not think much about it at the time, but looking back now, there might have been some racial undertones in their condemnation of his campaign.

Even more so, he remembers when a group of students told him that despite the color of his skin, he was OK, addressing him with a strong racial slur. Laconia said that, too, played into another level of naivete.

“Back then, I remember what I did was I gulped, like this was inconsistent with what I see Christianity being,” Laconia said. “I would say for a number of years when I got in touch with that, I allowed myself to feel the hurt and the pain and the anger. And then one day, I just woke up and I remembered the kindnesses.”

“And then one day, I just woke up and I remembered the kindnesses.”

He remembered the kindnesses of Chancellor David Burks and his wife Leah. He remembered former professor Bill White and his wife Neva, and he remembered Dan Cooper, a student who visited his home congregation during his senior year of high school and invited him to attend Harding.

“They embraced me as a human being,” Laconia said.

Burks said it was uncanny the number of students that Laconia knew when he was on campus, seemingly knowing every single student. Burks remembers Laconia’s kind-heartedness and strong spiritual devotion, a desire to “do what’s right in God’s eyes,” which left an impact on campus even years after he graduated.

“He got along with people regardless of where they were from or their income level or their background,” Burks said. “He treated everyone on campus as equal.”

“He treated everyone on campus as equal.”

Even though Laconia saw each of his fellow students as equal, he was also well aware that, just as good and bad exists in the world, good and bad also exists at Harding.

The good and bad came in recollection that was years removed from his time at Harding, despite whether or not he understood the racial implications of the time and of his election.

“I ran specifically as a person running for the office,” Laconia said. “I didn’t run to be the first black SA president.”

“I didn’t run to be the first black SA president.”

Now, 44 years removed from his office, Laconia said that Harding, and the world too, must come to terms with its own naivete and understand what history’s stories mean for the past, present and future.

“I would say, to Harding specifically, to be unsparing in looking at its own history with race,” Laconia said. “When I say to own that, I don’t mean to own it and say we’re proud of it. I mean to own it by looking at it offering opportunities for people to discuss it and then to move forward. I do think there is a tendency for Christian-oriented people, and specifically conservatively Christian-oriented people, to speak that things are never about race.”

“I would say, to Harding specifically, to be unsparing in looking at its own history with race,”

When those believers pull the “things are never about race” card, Laconia said it leaves gaping holes in recognizing a nation’s past wrongs, citing “The Half Has Never Been Told,” a book which explores how slave labor gave way to America’s becoming a superpower.

“If people who call themselves believers can participate and talk about how our own traditions participated in the issue of slavery and racism, then I think we can get somewhere,” Laconia said. “But if we can’t talk about that, I think we’ll be talking beside each other, but we won’t be talking with each other.”

“But if we can’t talk about that, I think we’ll be talking beside each other, but we won’t be talking with each other.”

In his own experiences, Laconia has found believers who are not afraid to have those conversations. After graduating from Harding, Laconia took to the Northeast United States where he worked in ministry and settled in Connecticut in 1985.

His ministry journey, influenced by the people he met along the way and the people he met at Harding, has allowed him to have conversations about mending the past and moving into the future. Naivete, it seems, is not so much a problem anymore for Laconia.

“My mind and heart have opened to the view that I look for Jesus in the life of every person with whom I come into contact, whether they believe in Jesus the way I do or not,” Laconia said. “My life has been transformed by that particular construct. It’s taken down barriers.”

“My mind and heart have opened to the view that I look for Jesus in the life of every person with whom I come into contact, whether they believe in Jesus the way I do or not.”

And those are not just barriers in his Christian community.

“I have friends who are atheist. I have friends who are Muslim. I have friends who are Jewish,” Laconia said. “When I look at them as fellow creations of God who can teach me something about God that I do not know, sometimes I have tears. That is still continuing, and I hope that continues until the day I die.”

Despite the fact Laconia’s life and Harding have seen many changes since he was a student, he remembers his first day on campus with affection.

“I think when I first stepped on Harding’s campus, the phrase I think I have is, ‘I was wide-eyed with wonder,’” Laconia said.

And looking back at his last day as a student, he remembers leaving with a “rich education” and a strong foundation on which his faith could stand.

“I think the job of a university is to give you the capacity, not just to see, but also to be able to have the freedom to ask the questions,” Laconia said. “If a university or a college does that — even if the students […] come to the conclusions that many of the faculty and administration come to, if the students get to ask the questions honestly and openly — then they have done a good job. And I think Harding has done a good job with that.”

For Laconia, a strong naivete has been vanquished by reflection and reconciliation. The way he chooses to perceive people, shaped largely by the experiences and lessons learned at Harding, has led to a greater understanding of how the world and younger generations can influence humanity, even when both good and evil exist.

“People who disagree with you — politically, religiously or whatever — they’re not the enemy,” Laconia said. “That’s what I would say. I would say that people have their beliefs for different reasons, and the challenge as a human being — indeed, the challenge as fellow created beings of God — is to get to know and understand the other person’s position.”

“People who disagree with you — politically, religiously or whatever — they’re not the enemy.”

Laconia could have, without a doubt, made many enemies in life and certainly during his years at Harding. His naivete could have been replaced by bitterness, and his memories of good could have easily been outweighed by memories of bad.

Instead, Laconia chose to remember the good — the boys in blue, Spring Sing, devotionals around the lily pool and relationships with professors. And along the way, he chose to embrace the bad — the racial slurs and prejudice — and ask the future to learn from it.

“In life, you have good and ill, and it depends upon not only what you remember but how you choose to remember,” Laconia said. “It doesn’t deny the darkness, but you can also choose to hold on to the light.”