On national adoption day, Nov. 18, 2017, President Bruce McLarty posted several pictures of those impacted by adoption on our campus. After seeing the large number of students, I decided to dig a little deeper into why people believe adoption is so important. This will be a three part series featuring stories about domestic and international adoption and foster care to adoption.

“Child to be adopted:

Christopher Michael Town-send. Natural Mother: Diane M. Townsend. Natural Father: Unknown … The State of Missouri to Unknown Natural Father, you are hereby notified that an action has been commenced … to obtain a decree of adoption of Christopher Michael Townsend, a minor.”

This excerpt from the April 1, 1976 edition of the St. Louis Countian declared the intended adoption of the man we now know as Dr. James (Jim) Miller, chairman of the Department of Communication.

Miller was adopted when he was 6 weeks old. Three years later, his parents adopted another child, Jeanne.

“I have always felt there was something special about being adopted. In some ways, I was chosen,” Miller said. “God provided me many great opportunities because I was adopted by a loving, caring, God-fearing family.”

Miller, one of 7 million adopted Americans, believed God’s hand was in his adoption story.

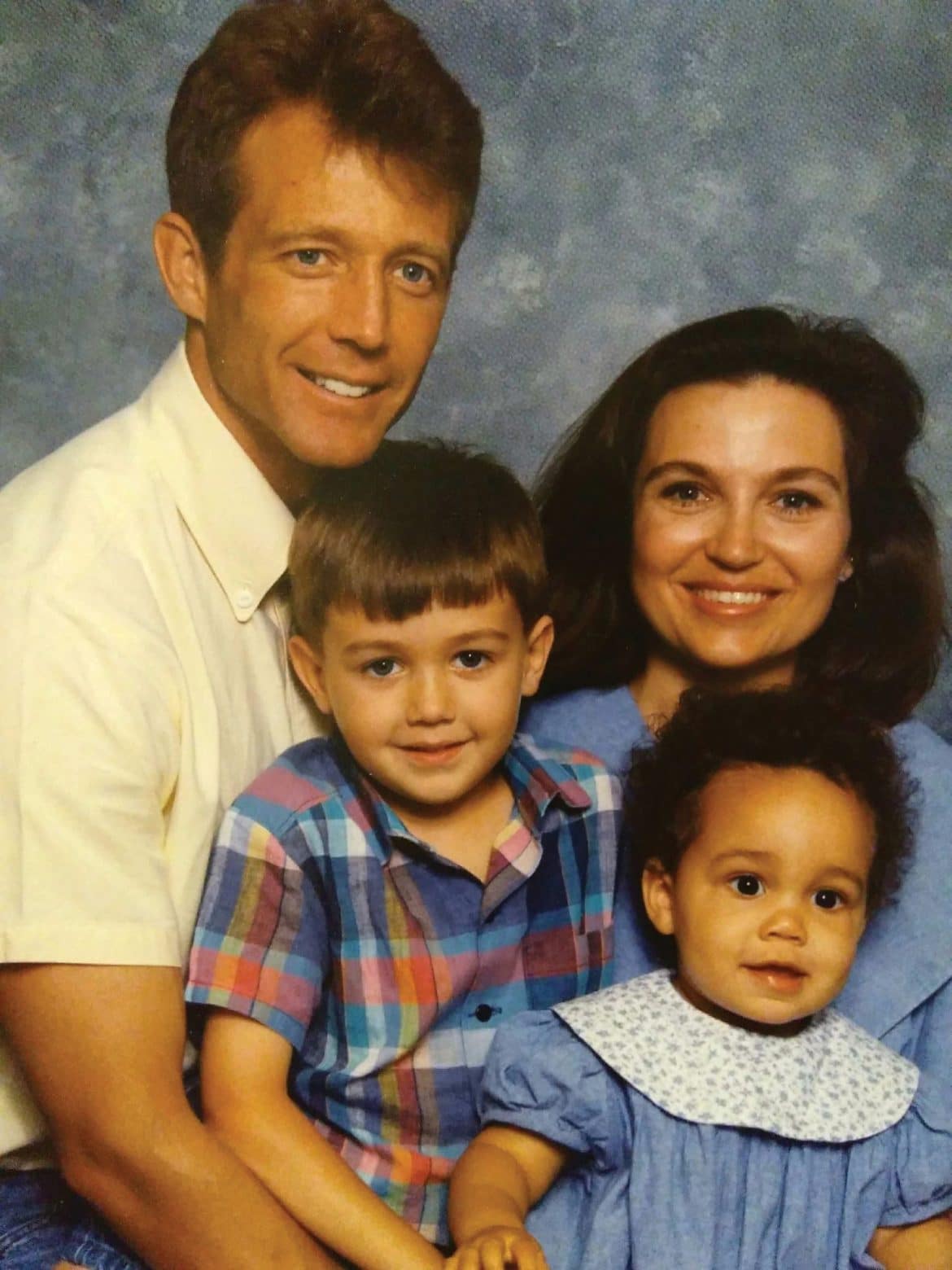

According to math adjunct professor Darla Phillips, and her husband, professor of exercise and sports science Bryan Phillips, God played a vital role in the adoption of their daughter as well.

The Phillipses began the adoption process after hearing from a colleague about a little girl who needed to be adopted. Seven months later, when their paperwork was finished, that same little girl was still available for adoption.

“Getting Kathryn was a godsend. We hadn’t thought that was a possibility,” Bryan Phillips said. “Normally a child would have been adopted by then, but Kathryn had to go through some court procedures that took time, and so the other couples ahead of us had already adopted other kids. …We ended up getting the little girl that spurred us on to get ready for adoption.”

Darla Phillips added that she believed God’s hand was in more than just the timing of the adoption.

“Her birth mother wanted her to be placed with an African-American family since her birth father was African-American. She felt she’d be more accepted if she was in a black family,” Darla said. “(But) no one on the (adoption) list wanted a biracial child. Kathryn was biracial. We didn’t really know what that meant. Biracial could be half Indian, half Caucasian. She happened to be half-black, half-white.”

Kathryn Phillips grew up in a predominantly white school and faced what her father referred to as “unintended bias.”

“At no point since the adoption has Kathryn been anything but our kid,” Bryan Phillips said. “We don’t see her as having color to her skin or anything, but you walk (through) Walmart and (people) don’t realize she’s our daughter. She’d run out in front of us and someone would grab her and say ‘Are your parents around?’ and we’re standing right there, but they wouldn’t know that.”

According to junior Jon

-Michael Fields, who was adopted shortly after birth, dealing with racial prejudice was common for him and his family. Fields, as well as two of his four siblings and both of his parents, were adopted.

“My family is very multi

-ethnic,” Fields said. “If you get a picture of my family with my extended family, we look like a bunch of random people. … One of the things that we were kind of taught growing up was that your skin color doesn’t matter, but people think it does.”

According to Kathryn Phillips, she faced hard situations due to her adoption fairly often growing up.

“I’ve had people tell me that my parents are not my parents because they didn’t give birth to me,” Kathryn Phillips said. “That was hard because I know that they’re my mom and dad, and they tell me that they’re my parents.”

Junior Riley Rose, who was adopted at 6 days old, faced similar struggles.

“Growing up, I had the mindset of being abandoned and unwanted,” Rose said. “It took me a little while to finally grasp that God planned this out for me. God chose to put (me) in the Roses’ hands in order for (me) to grow up in Searcy with them as (my) parents and Wil as (my) brother.”

Rose added that being adopted gave her opportunities that she would not have had otherwise.

“I needed someone to nourish me spiritually, emotionally, physically, mentally and (my parents) did that,” Rose said. “They fed me when I don’t know if I would have been fed before. They gave me a bed, (when) who knows if I would have had a bed before. They gave me a house. They gave me an opportunity to be educated. They gave me my best friend — my brother. All those things no one ever thinks about.”

Fields believes that those provisions made by adoptive parents for their children are a result of a “special crazy kind of love.”

“The most high love, the ultimate love, is the love of choice,” Fields said. “I say ‘I am going to choose to love another person with all my being.’ That is what adoptive parents do. They take you in, they say ‘you are not my own, but I am going to love you like you are.’ Through that, you become their own.”

Miller believes that crazy kind of love is what God has for his people, and why adoption is so meaningful.

“Scripture talks a lot about adoption and that should not go unsaid,” Miller said. “Paul writes about how all of us are adopted sons and daughters and there’s something really special about that. Where God has chosen us to be his children, to lavish on us so many great riches that come with being a part of his family. …We’ve all been chosen. That’s significant. We all want to be wanted and loved and chosen — and we are.”

This is the first installment of the “Chosen” series. The second will appear in the next edition of The Bison, on stands, Jan. 26.