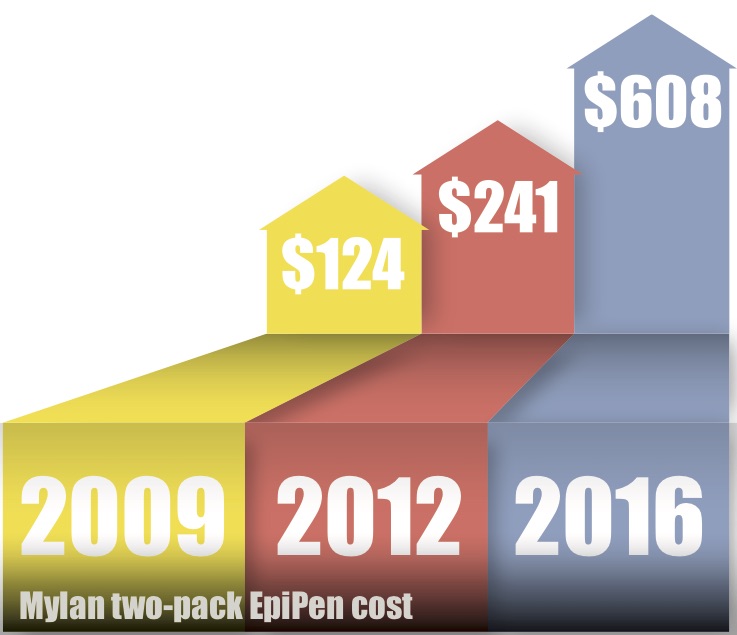

EpiPen, owned by pharmaceutical company Mylan, is the only FDA certified epinephrine auto injector on the market. In 2009, a two-pack of EpiPens sold for $124, according to Forbes Magazine. At the end of 2012, the price rose to $241. Today, a two-pack of EpiPens sells for $608.

Mylan now makes 40 percent of its total profits from the EpiPen, that is a $1 billion annual profit from an injection that uses less than $1 of epinephrine.

Researchers at the Food Allergy Research & Education (FARE) organization have found that nearly 15 million people in the United States are affected by food allergies. When coming to Harding in the fall of 2013, senior Amy Davis was one of those 15 million, having been just diagnosed with an allergy to tree nuts. With her diagnosis, her doctor gave her a prescription for an EpiPen — an injection containing epinephrine, a hormone which opens up airways in the lungs during a severe allergic reaction.

According to Chair of Harding’s Graduate School of Business, Glen Metheney, Mylan did what most companies dream of achieving from a business angle: taking a basic product and turning it over for a great profit. Mylan used public awareness campaigns and education on the dangers of child allergies and created a successful product.

“It is maybe price gouging, but it’s also a free market,” Metheney said.

In January 2013, a competitor to the EpiPen which was released, Auvi-Q, which listed at the same price as the EpiPen, according to Forbes. Six months after Auvi-Q’s release, EpiPen raised its cost from $241 to $265 in July of 2013. Two weeks later, Auvi-Q’s list price went up to $277. In November 2013, EpiPen raised its price to $304, and in December, Auvi-Q’s price went up to $334. By the time Auvi-Q recalled in 2015, its list price was $509, while EpiPen’s was $461.

According to the FARE website, every three minutes a person is sent to the emergency room due to a food-related allergic reaction.

“Thankfully, I’ve never had to use my EpiPen,” Davis said, “but I have one that talks you through what to do; it actually has a little Siri in there telling you what to do.”

Although Davis has an unused EpiPen, she is still affected by the price-raise.

“I’m going to need to get a new one since they expire,” Davis explained. “I am frugal at my core, and I’m a poor college student; I’ll probably just not get one. Fingers crossed I don’t eat any cashews.”

The sticker shock of EpiPen is forcing many people — even those who don’t use the product — to seek other options or not purchase epinephrine at all. There are currently three products on the market in the United States: EpiPen, Adrenaclick and Epinephrine authorized generic. EpiPen has a patient assistance program that allows customers 200 percent under the poverty line to receive the product for free, as well as a Mylan savings card that saves customers up to $300, depending on their insurance. Andrenaclick is an auto-injector similar to EpiPen, and depending on insurance, copays, and manufacturer coupons, a two-pack of Adrenaclick can cost as little as $140.