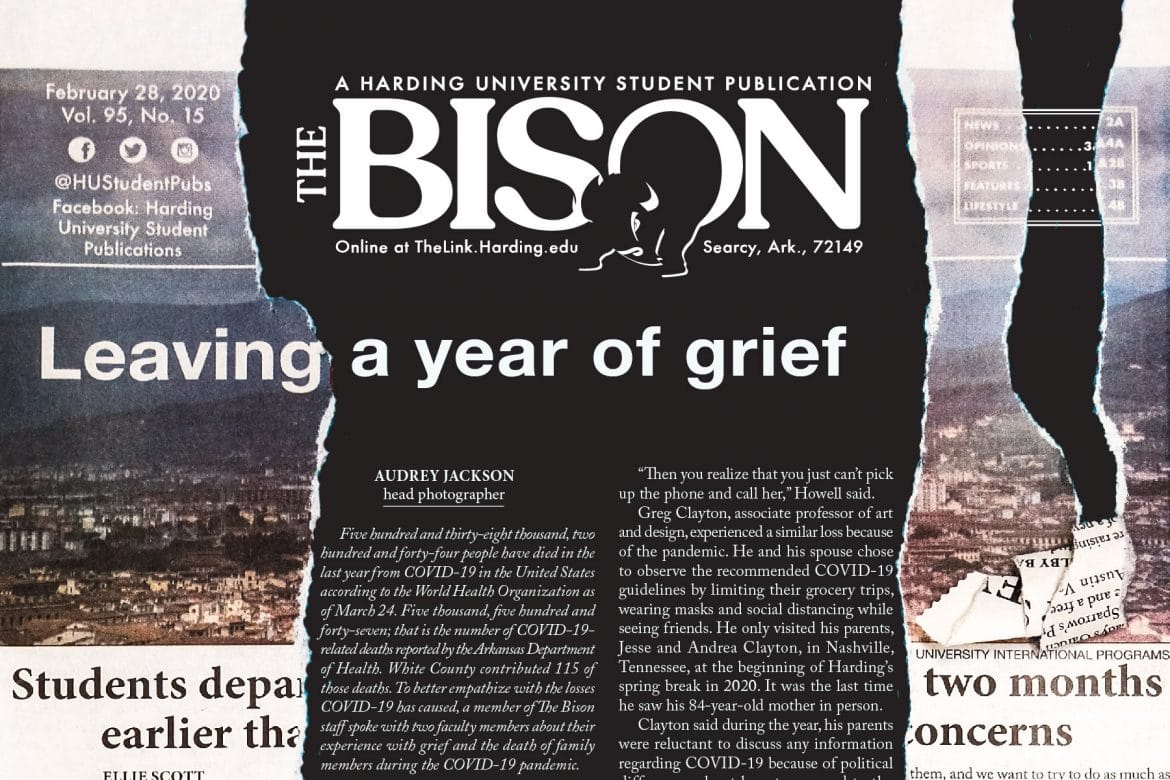

Five hundred and thirty-eight thousand, two hundred and forty-four people have died in the last year from COVID-19 in the United States according to the World Health Organization as of March 24. Five thousand, five hundred and forty-seven; that is the number of COVID-19-related deaths reported by the Arkansas Department of Health. White County contributed 115 of those deaths. To better empathize with the losses COVID-19 has caused, a member of The Bison staff spoke with two faculty members about their experience with grief and the death of family members during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Harding University announced on March 12, 2020, that the campus would close and classes would transition online until further notice after the confirmation of the first COVID-19 case in Arkansas. Dr. Byron Howell, assistant professor of graduate business administration, recalled how temporary the initial announcement felt. He expected things to be OK after a month or two.

“At the time, it seemed like such a short-term thing that we could get over the hump on,” Howell said.

Howell and his spouse strictly followed the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID-19 guidelines. Grocery pickup became their norm. Restaurant takeout broke up the monotony of home-cooked meals. Then in the fall, Howell’s mother and brother both died of COVID-related complications.

Ruth Howell, Byron Howell’s 96-year-old mother, contracted the coronavirus while living with family members in Millington, Tennessee. After her hospitalization, one of Byron’s nephews was allowed to visit her and facilitate a video call before she died on Aug. 19, 2020. The family scrambled to notify everyone they could to join the call.

“It’s not the same as giving a hug,” Howell said.

The Howell family opted for a graveside memorial service since they were unable to have a funeral service. Howell and his spouse traveled to Memphis, Tennessee, in their RV and parked near the grave to watch the livestream, avoiding exposure to family who had recently had COVID-19. Howell took a picture of the pallbearers carrying the casket to the grave and showed it to his class the next day.

“This thing is real, you know,” Howell said to the students. “You may feel sort of bulletproof because you’re young and, fortunately, it doesn’t have such an impact on young people, but it does on your grandparents and parents.”

Howell’s 76-year-old brother, Bruce Howell, died four months later on Dec. 31 from COVID-related pneumonia, which he contracted while living in a nursing home. Howell said the family has planned a reunion for Oct. 12, 2021, his mother’s birthday, to celebrate the memories of his mother and brother. The grief has permeated his life through habits and small reminders, Howell said. He found himself reaching for the phone to call his mother for weeks and months after her death, wanting to share prayer requests and events from his day.

“Then you realize that you just can’t pick up the phone and call her,” Howell said.

Greg Clayton, associate professor of art and design, experienced a similar loss because of the pandemic. He and his spouse chose to observe the recommended COVID-19 guidelines by limiting their grocery trips, wearing masks and social distancing while seeing friends. He only visited his parents, Jesse and Andrea Clayton, in Nashville, Tennessee, at the beginning of Harding’s spring break in 2020. It was the last time he saw his 84-year-old mother in person.

Clayton said during the year, his parents were reluctant to discuss any information regarding COVID-19 because of political differences about how to respond to the pandemic. His mother eventually told Clayton and his three siblings that she had been tested for COVID-19 in November 2020.

The response, he said, was a shock. The family wrestled with how to respond and intervene from a distance. How could they motivate Mom to get care when she saw herself as a fairly strong, independent woman?

“There’s a certain ego sacrifice involved in giving up and going to the ER, and some of us resist getting healthcare — myself included,” Clayton said. “Though she was much more willing to get healthcare generally, the politics of COVID had complicated the willingness to admit she needed that kind of care.”

After considering several options — calling an ambulance or having someone drive them to the hospital — Clayton’s brother, who lived near their parents, drove over to check on them and, ultimately, took their mother to the emergency room. Within two weeks, their mother had died. While the hospital only allowed two siblings to be with their mother when she died, Clayton was able to be present remotely.

“The only way I visited mom was a phone call,” Clayton said. “There were some options for a video call, but she was a Southern lady, and showing herself all wired up and tubed up with a ventilator was something she didn’t want, so we only had a couple phone calls.”

Clayton’s father, Jesse, died 12 days after his wife. Though his father’s health had been declining slowly since a stroke five years prior, the family believed that a mild case of COVID-19 and the loss of his wife contributed to his death.

Clayton said the shock the family experienced was indescribable. His parents went from living alone and being self-sufficient to gone within a month. Rarely does a week pass without two or three reminders of their death, Clayton said.

Both professors spoke of the importance of speaking to others who shared their experience and relying on their faith while processing their grief. Clayton said it was important to understand that grief is not always visible, and people should treat others with patience. Grace was an important aspect of supporting others in their grief, Clayton said.

To view this special edition in newspaper format, click here.