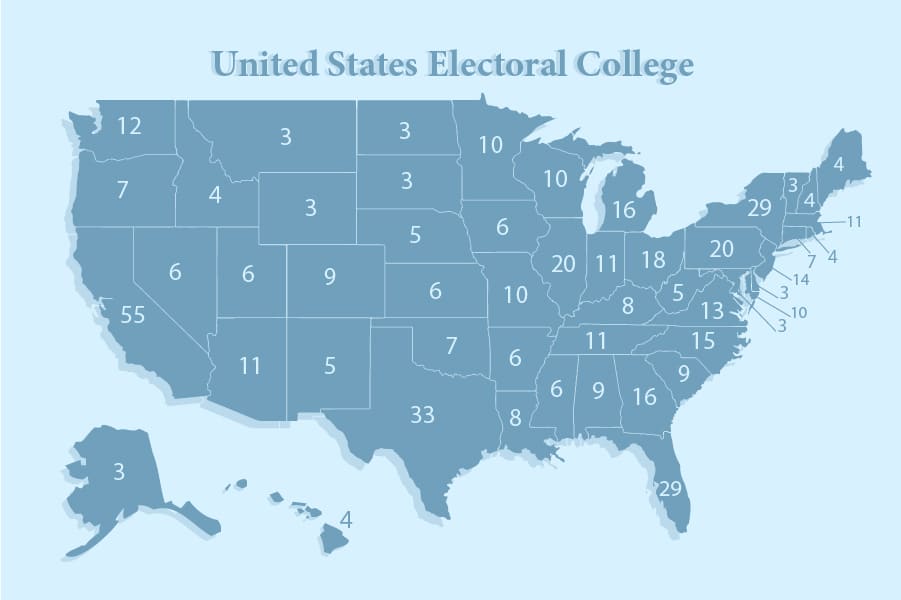

On Dec. 14, the United States Electoral College will meet to certify the results of the 2020 presidential election. Democratic nominee and former Vice President Joe Biden is the winner of the election with a projected 306 electoral votes to President Donald Trump’s 232 electoral votes. Although President Trump has alleged that a large amount of the votes cast were fraudulent, there has yet to be evidence produced to support these claims, and almost all of Trump’s legal challenges have been struck down by judges.

Due to these allegations and a week-long vote counting process, several Harding students have expressed confusion about the electoral process and whether their votes really matter. Senior Lucas Lawrence, who voted in the 2020 election, expressed confusion as to why his vote seemingly does not matter in the long run.

“I think that it creates some dissonance that the popular vote does not always guarantee the winner,” Lawrence said. “The whole system can really feel convoluted and confusing and break the straightforwardness of the whole ‘just vote’ idea.”

This confusion has led to a renewed interest and discussion about whether the Electoral College is good for American politics. Assistant professor of history and political science Lori Klein argued that the Electoral College has done more positive than negative, and that it reflects a key idea in American politics.

“You get the number of electors based on how many House members you’ve got and how many Senate members you’ve got, so it reflects in the count the original bicameral compromise between the House being population-based and the Senate being an equal number per state,” Klein said. “That’s why we have an electoral structure like we do. The small states want to make sure they don’t get run over by the big states, and the big states want to make sure … the small states aren’t riding along on their coat tails.”

However, not everyone is in agreement with Klein. Junior public administration major Bennett Anderson said the system creates power imbalances during elections.

“Voters who are a political minority in their non-swing state feel like they have no say in the election, and a handful of battleground states ultimately [determines] the election’s outcome no matter how strongly most voters preferred the other choice,” Anderson said. “The Electoral College suppresses voters’ trust and confidence in their ability to make meaningful change in their government.”

Klein said that she understands these frustrations and the key to changing the Electoral College is more in the people’s hands than they realize.

“If you don’t like the Electoral College, the chances of changing it nationally are slim, but you could change the way your state counts the electorate,” Klein said. “Citizens’ initiatives come from the people and are sent to the legislature for approval. If you want to change the electorate, focus on your state.”