The Brackett Library contains thousands of books. In her four years working at the library, senior Paige Cushman has mended over 1,200 of them.

Cushman began working in the library archives her freshman year alongside alumna Emily Peterson. Intrigued by Peterson’s job as book mender, Cushman asked if she could learn to repair books. By her sophomore year, Cushman found herself employed as the new book mender.

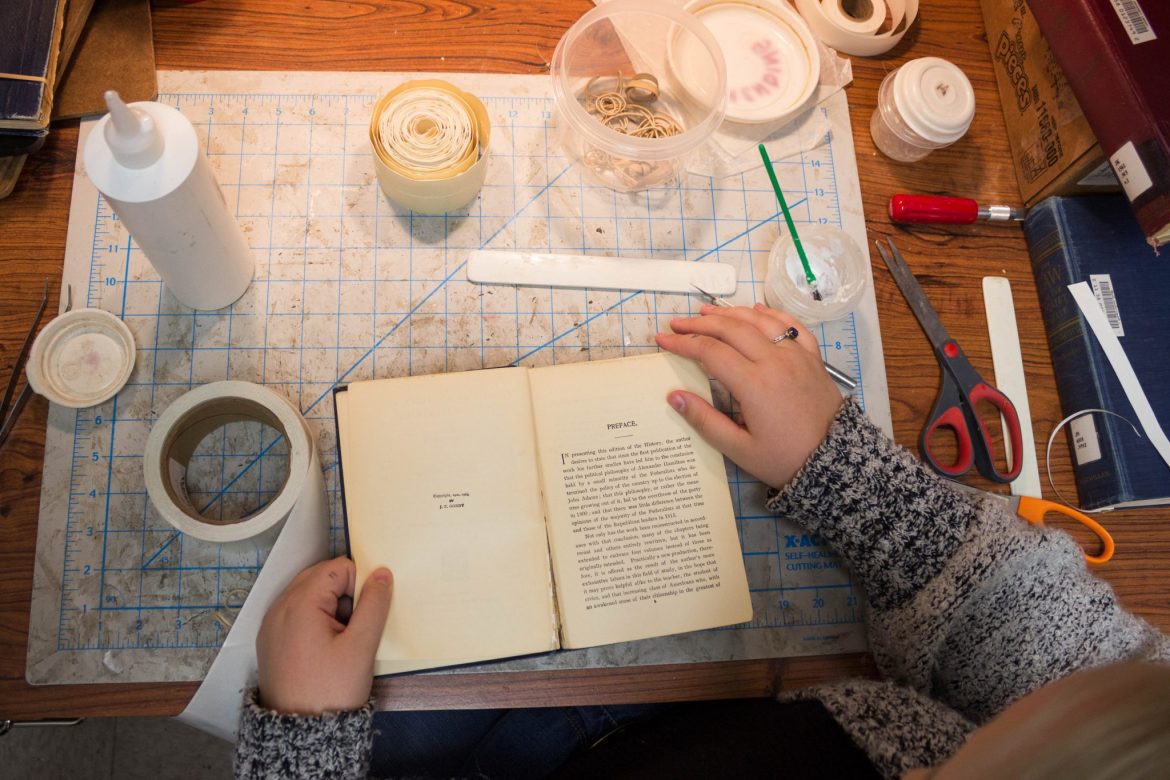

Two years later, Cushman is still cutting, taping and revitalizing books for the student body to use.

“It’s really gratifying to make a decrepit book functional and beautiful again,” Cushman said. “It gives me a reason to work with my hands and channel my creative energy into something productive.”

According to archives and special collection librarian Hannah Wood, book menders like Cushman provide great value to the library.

“Having book menders in-house extends the lives of many books that we might not be able to replace,” Wood said. “Some books are out of print. Finding a replacement may not be possible; therefore, we need to make the copy we have last as long as possible. A book that is one volume in a series may not be sold by itself. We would have to purchase the entire series to replace that one volume. That is cost prohibitive. Some books cost hundreds of dollars (mending) it makes financial sense.”

Every week, Cushman mends about 30 books. Repairs range from taping torn pages to replacing spines. Cushman said in addition to the different X-Acto knives, glues and tapes she uses on a daily basis, she uses a small “book iron” to flatten the tops of old cloth books.

“Book mending, to me, is pretty much adult arts and crafts,” Cushman said. “I cut myself with scissors at least once a week; I get glue on everything; I get to play with power tools; I tear apart books daily; and I always leave with paper scraps stuck to me.”

For two years, Cushman was the only one on campus who knew how to do her job — until she taught junior Taylor Wilkins.

As a history major, Wilkins enjoyed the historical aspect of preserving books and feels the job has prepared her for work in other archives in the future.

“I like the aspect that each book is like a project, and it feels great to get it all fixed up and back into circulation,” Wilkins said. “It’s also really neat to be able to have this skill and be trusted with such old, special books.”

Wilkins said the oldest book she ever mended was an old hymn book from 1856, but the majority of books that need mending are anywhere from 20-60 years old. Wilkins said what keeps the job interesting is the uniqueness of every book she mends.

“No book is alike,” Wilkins said. “We learn different techniques, but you have to constantly adapt them to each book. Some books are too delicate, or too big or in such bad shape that you really have to think through what you’re going to do in order to be able to put it back together and preserve it for future readers.”

Wilkins said of all of the books she has mended, her favorite was one that had a particularly surprising topic.

“I had this tiny little book, only about 6 inches tall and it had the sweetest little flower design,” Wilkins said. “It was from the 1920s. I looked at the title to see what it was, thinking it was some little short stories book, but it was actually ‘A Short History of the Civil War.’ I loved it because that is one of my favorite time periods to study, and the book was just too cute.”

According to Woods, book mending is not the only unique job offered by the library.

“I would say that about 40 percent of jobs performed by our student workers are jobs the average student isn’t aware of,” Wood said. “Library student workers are processing newly purchased books, searching for lost books, scanning photographs or papers like the Student Association minutes from the 1950s and 1960s and creating code for online databases like the Harding Remembers project.”

Written by Zach Shappley and Raianne Mason