Universities nationwide are using dashboards to provide COVID-19 information for their campuses and the public, as well as to promote transparency, and on Oct. 15 the Arkansas Department of Health (ADH) reported Harding University as having the highest number of active COVID-19 cases among Arkansas universities. Harding reported 92 active cases that day, and the University of Arkansas (U of A), dropping from the top to the third highest cases on campus in Arkansas, reported 48.

Different testing methods on university campuses have influenced how information fluctuates on university dashboards. Harding suggests only those who have symptoms and those who are close contacts of positive cases be tested at Student Health Services (SHS). Harding advises individuals to get tested at a local clinic in Searcy if they are asymptomatic and are not a close contact of a confirmed case. Positive results from locations outside of Harding, when they are reported back to the school from ADH, are included in the numbers recorded on the dashboard. Other universities, including the U of A, follow other CDC guidelines, encouraging testing of asymptomatic people on campus and include the number of those who get tested off campus in their statistics.

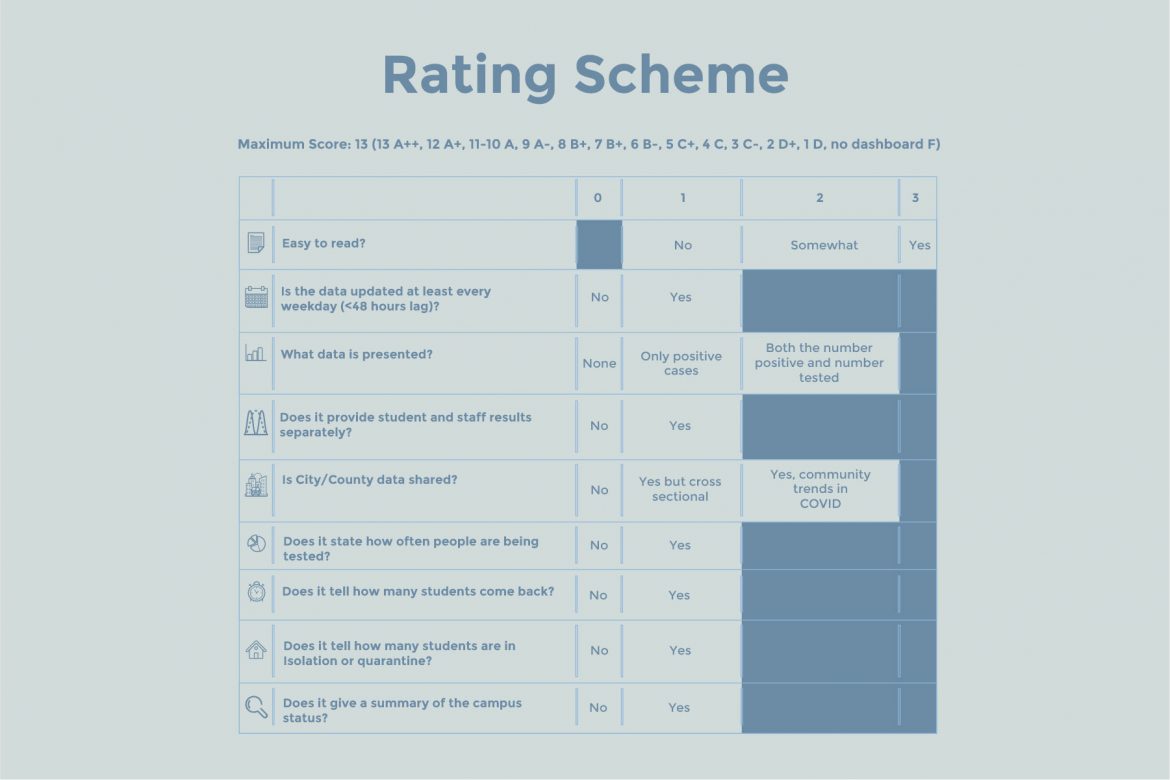

The way testing is done in each school is reflected in the way statistics are presented on the university’s dashboard. Dr. Howard Forman, professor of radiology and biomedical imaging and public health at Yale University, conducted research on the different COVID-19 methodologies of testing and reporting. Forman and his team developed a rating system and gave ratings to over 200 institutions based on their dashboards, A+ being the highest grade, and F being the lowest. According to Forman’s rating scheme, Harding’s approximate rating would be a B-.

Vice President for University Communications Jana Rucker said Harding’s testing method limits what their dashboard looks like. She said they chose to test symptomatic people and close contacts, so they do not add the total number of specimens collected by SHS to the dashboard or a positivity rate because it is not an accurate representation of the student body.

“The more straightforward numbers, of course, are the numbers of the individuals who are in isolation/COVID-19 positive and in quarantine/close contacts of a COVID-19 positive individual,” Rucker said.

Those are the numbers presented on the dashboard. Associate professor of communication Jim Miller said, though knowing the number of tests completed provides the percentage of positive cases, the fact that people get tested outside of Harding skews those numbers.

“There’s not necessarily a way to know how many tests are being done every day,” Miller said.

Differing testing methods proved to show early spikes in cases over the semester for some schools and later for others. Three weeks into the fall semester, U of A had an average of 648 active cases, while Harding had a total of 12. U of A had a more open testing policy and had more specimens collected sooner. As of Oct 19. Harding reported 514 test results, and U of A reported 10,389.

People across the nation grew to expect dashboards as a platform for general COVID-19 statistic reporting, but methods for receiving information varied on Harding’s campus. Before utilizing a dashboard, Harding sent out three campus wide emails providing students and faculty with COVID-19 statistics on campus. After a number of inquiries about more frequent updates, Harding announced on Sept. 10 COVID-19 updates would be posted on an online dashboard at noon each day beginning the following Monday. Harding sent the final campus wide COVID-19 status email on Sept. 14, announcing updates would be exclusive to the dashboard unless circumstances changed. Digital Media Coordinator Megan Stroud updates the dashboard and enters the new numbers every weekday. She said Harding made the switch to the dashboard to make information more readily available and easy to access.

The switch to the dashboard resulted in less daily information sent to students’ inboxes, and some students reported the inconvenience meant they had to search for alternate methods of acquiring information.

Junior Grace Tandy said she believed Harding stopped giving out information simply because she stopped receiving information directly. She said Instagram became the platform she used for COVID-19 updates.

“I receive the info from Stu Pubs’ Instagram account,” Tandy said. “It is easily accessible.”

Social media became the primary source of information for senior Quinn Brandt, too. He said the initial emails Harding sent out with status updates allowed him to manually track the progression of the numbers of those isolated and quarantined on campus. When Harding limited their reporting to a dashboard with a current status of campus, he started relying on the Instagram account @covid_on_campus to keep him up to date with history graphs for every update released by Harding.

“Just looking at a single day’s numbers doesn’t tell you much when it’s up 20 from two days ago, or when it’s down 20 from two days ago,” Brandt said. “Just looking at those numbers without any history of where they’ve been doesn’t really tell you whether or not we’re turning upwards or downwards, or whether or not we expect those 70 people are going to be out of quarantine next week.”

Brandt said numbers in context provide information that allows people to see what it actually means for their current situation.

“There are ways to put the data into context better for students to quickly and easily identify potential danger on campus better than what it is right now,” Brandt said.

Assistant professor of mathematics Laurie Walker said she looks at the dashboard every day, and loves the accessibility of the numbers, but she would like to see more than the numbers given.

“I think percentages would give a better sense of how the Harding community is doing and enable us to compare ourselves with other communities,” Walker said.

Professors across campus said they value Harding’s transparency with reporting COVID-19 numbers. Professor of mathematics Travis Thompson said the daily weekday update of quarantine and isolation numbers is informative and helpful, though he said the numbers on the dashboard are not necessarily statistics because they are numbers that stand alone day to day. Statistics are derived when a target population is sampled and an “estimate of reality” is represented, Thompson said. He said numbers representing how many students are quarantined are not a statistic because they are an exact number and not an estimate.

“There are other numbers that could be presented on the dashboard, but I think the present format and information displayed is both necessary and sufficient,” Thompson said.

Miller said he thinks the University has done a good job of reporting the daily numbers that are helpful to those on and off campus, though more information made available to the public is always better in matters concerning public health.

“To whatever extent we can continue to be transparent in our reporting of numbers — whether [or not] that’s testing that’s done on campus — the more transparent we can be, the better,” Miller said.